2 / 5 Stars

All of the stories in this chunky (349 pp., 9 pt type) anthology were published in 1969, many in magazines such as ‘Analog’, ‘Galaxy’, and ‘Fantasy and Science Fiction’.

My capsule reviews of the contents:

SO....what's a PorPor Book ? 'PorPor' is a derogatory term my brother used, to refer to the SF and Fantasy paperbacks and comic books I eagerly read from the late 60s to the late 80s. This blog is devoted to those paperbacks and comics you can find on the shelves of second-hand bookstores...from the New Wave era and 'Dangerous Visions', to the advent of the cyberpunks and 'Neuromancer'.

3/5 Stars

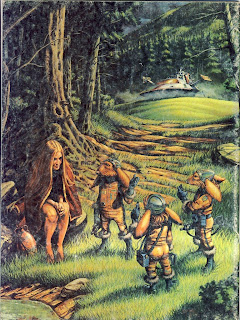

3/5 Stars‘The Hunters’ was first published in 1978; this Playboy paperback edition (223 pp.) was issued in 1979. The cover painting, evoking the box-office hit ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’, is by V. Segrelles.

In the small town of Bear Paw, Montana, a strange couple appear in town one day and give a 'Saucer Cult' presentation to skeptical townspeople: a journey to the stars, true enlightenment, and spiritual fulfillment, are theirs for the taking. Many townspeople are deeply moved by the presentation and the next morning, they gather in the town square in preparation for the Journey. An unusual silver bus arrives, and the couple welcome the earthlings aboard. The bus moves smoothly and silently out into the countryside, ultimately arriving at the ruins of a ghost town from the 19th century. The passengers debark, climb to the top of a nearby hill, and witness an enormous flying saucer.

The people from Bear Paw are amazed and awed by this display of technology and when the vessel lands, they prepare to board, singing hosanahs to the Star People. But it suddenly becomes unpleasantly clear that the aliens aboard the saucer are not benevolent. In fact, they are looking forward to sport….of the hunting kind. And the townspeople of Bear Paw are their quarry.

‘The Hunters’ is a pulp SF novel that was plainly written to cash in on the marketing excitement of ‘Close Encounters’ and the attendant UFO craze of the late 70s, as well as SF thrillers like ‘Alien’. The movie ‘Predator’ was still 9 years in the future, and it’s unclear if ‘Hunters’ influenced Jim and John Thomas, the screenwriters of Predator. Unlike the alien featured in Predator, in ‘Hunters’ the aliens are more humanoid in appearance and possess unique personalities; they also lack the impressive firepower and cloaking technology of the Predator. But they nonetheless remain formidable adversaries.

The townspeople are the usual motley collection of stereotyped individuals. We have some Commune-derived hippies; a quarreling married couple; an Indian couple fond of giving portentous, ‘Black Elk Speaks’ – style speeches to the unworthy Palefaces; a family of crazed Christian fundamentalists; the town drunk; and BadAzz Mofo Sam Tolliver, who can’t pass up a chance to mess with Whitey whenever there’s a lull in the action.

Authors Wetanson and Hoobler have a tendency to write lame passages of dialogue, much of it dealing with homespun philosophy and psychodrama, for the townspeople to engage in at inopportune times. I often found myself exasperated by the witless nature of some of the characters. But the encounters between human prey and alien hunter come with enough frequency and bloodshed to move the story along at a good clip despite these literary drawbacks. In its last 20 pages the narrative is genuinely engrossing, and the authors refrain from tipping their hands in terms of indicating who will ultimately triumph.

Readers interested in an entertaining, if not particularly original, SF adventure may want to give this book a try.

5/5 Stars

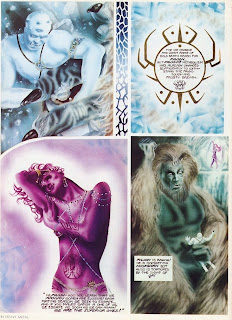

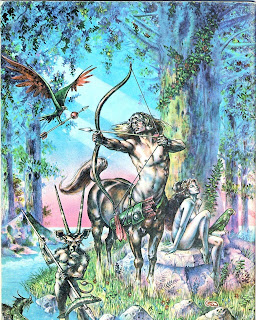

5/5 StarsThis month’s cover is ‘The Wizard of Anharitte’ by Peter Andrew Jones, and the back cover is ‘Centaur’s Idol’ by Clyde Caldwell.

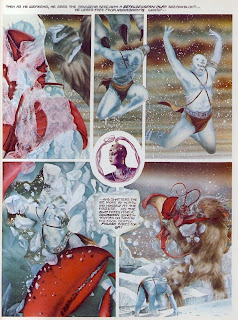

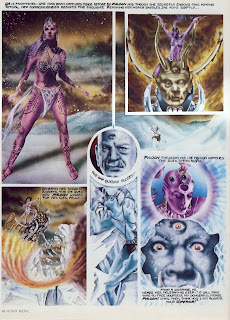

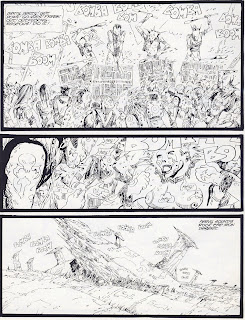

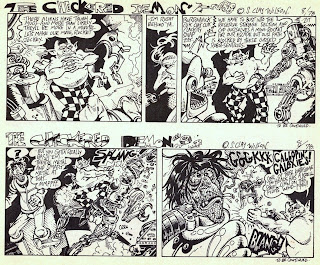

I’ve scanned two shorter entries (that hopefully won’t imperil my Blog’s ‘PG’ rating with Google):

One entry is ‘Night Angel’, by Paul Abrams, definitely a trippy ‘stoner’ tale with some moody, effective artwork.

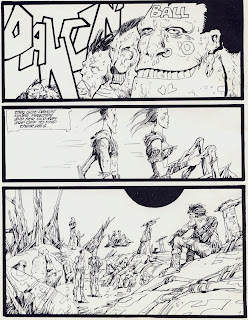

The other entry is one of Philippe Druillet’s occasional non- Lone Sloan pieces to show up in Metal Hurlant, ‘Dancin’ Ball’. (I’m not sure how well the thin-line, rather spidery pen-and-ink artwork will appear onscreen even with a 200 dpi scan, but I want the pages to load in a reasonable length of time). ‘Ball’ is a very cool take on futuristic bikers and wanton violence with a cynical twist of an ending.

5 / 5 Stars

5 / 5 Stars

2 / 5 Stars

2 / 5 Stars 4/5 Stars

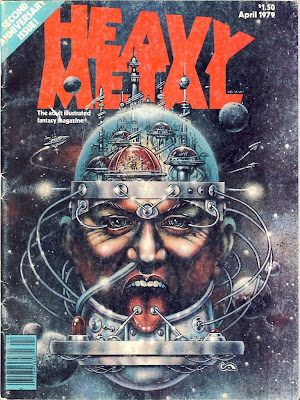

4/5 StarsThis April 1979 issue of ‘Heavy Metal’ is noteworthy for featuring a preview of the Fox SF-horror blockbuster ‘Alien’. The film, which had a budget of close to $ 10 million ( a lot of money back in 1979) was due in theatres in early Summer. 20th Century Fox was obviously hoping to cash in on the momentum generated by ‘Star Wars’, ‘Superman’, and other SF films of the past two years that had yielded unprecedented box-office receipts.

Being chosen to publicize the film was a real coup for Heavy Metal, which had been in print for two years, but was still struggling to gain advertising and some perception of legitimacy among the ‘mainstream’ print media. That Fox executives had decided to give a somewhat obscure ‘stoner’ magazine the licensing rights for their marquee film for the year had to be encouraging to the magazine’s owners, The National Lampoon. Indeed, by selecting Heavy Metal to showcase their film among what would come to be labeled the ‘fanboy’ crowd, Fox was engaging in a marketing practice that was still comparatively innovative at the time. Nowadays, nobody blinks when directors and cast associated with a high-budget SF or fantasy blockbuster appear at various Comic-Con shows to preview clips and take questions from the audience. But the idea of dispatching Ridley Scott or Sigourney Weaver to speak at a geek gathering would have gotten a Fox marketing exec fired back in ‘79.

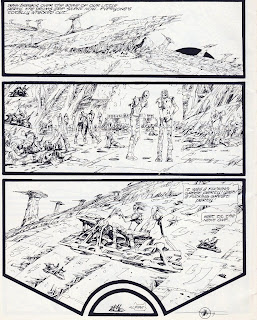

Along with some pages from the Alien preview, I’m posting ‘Pyloon’, a tongue-in-cheek homage to SF illustration, with art by Ray Rue and a script by Leo Giroux, Jr. I’m sure readers will find at least one archetypal image that they recognize as cribbed from the visual library of pop culture and SF. The art is very good, particularly when one realizes that computer-generated color separations were still years away.

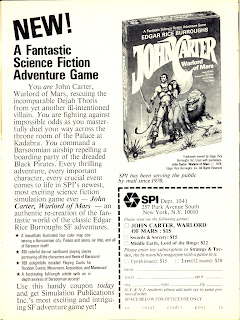

Also posted is a advertisement for a board game, ‘John Carter of Mars’ , by SPI, one of the leading publishers (along with Avalon Hill) of war games, and other hex-based board games, during the 70s. This is what you got when you went ‘gaming’ way back then. ‘Space Invaders’ had still not appeared in my hometown in upstate New York in April of ’79, and the idea of playing games on ‘micro-computers’ was something electrical engineers thought about in their spare time, when they were hypothesizing about home entertainment in the 21st century.

Rounding out our look at the April ’79 issue are the front cover by Clyde Caldwell (‘The Brain Cloudy Blues’), and the back cover by Larry Elmore (‘Gidget Meets the Squirrel Dogs from Outer Space’).